I’ve become immersed in the world of Mihail Sebastian after reading his novel For Two Thousand Years, his pamphlet How I Became a Hooligan, moving straight onto his Journals, which take up where the previous two left off (1935-1944). I would continue with his plays and novels too, but sadly they are buried somewhere in my parents’ shelves in Romania.

In many ways, Sebastian was the Romanian Orwell, remarkably clear-eyed about politics and social justice, not prone to extremes, and with the ability to articulate so well the pain of the world that he lived in. I have so much to say about him and his writing, that I will dedicate several posts to him.

First, a little bit of background. Mihail Sebastian was born Iosif Hechter, in a Jewish family in the port town on the Danube Braila in 1907. He went to study Law in Bucharest (and Paris) and soon became involved in the lively literary and artistic milieu at the time, which included Mircea Eliade, Emil Cioran, Eugen Ionescu, Constantin Noica, Camil Petrescu, Cella Serghi and Geo Bogza.

I was born in Romania, and I am Jewish. That makes me a Jew, and a Romanian. For me to go around and join conferences demanding that my identity as a Jewish Romanian be taken seriously would be as crazy as the Lime Trees on the island where I was born to form a conference demanding their rights to be Lime Trees. As for anyone who tells me that I’m not a Romanian, the answer is the same: go talk to the trees, and tell them they’re not trees.

Like most of his contemporaries, he fell under the spell of charismatic philosophy professor and journalist Nae Ionescu, who convinced him to join his journal Cuvântul, which became one of the cultural trendsetters in the late 1920s. Sebastian published two volumes of prose in the early 1930s but was generally better known as a theatre and music critic. And then he wrote the novel For Two Thousand Years, in which he describes what it was like being a Jewish student during that period in Romania. I’ll discuss that book in more detail in another post, but here is the back story of how he became notorious.

He asked his favourite professor and mentor for a foreword to his novel and Nae Ionescu unleashed one of the most virulent anti-semitic attacks on his protégé that you could possibly imagine. Devastated by this betrayal, and after much soul-searching, Sebastian decided to publish the book with the preface. It became the most talked about, scandalous book of 1934, with the author being accused of being both right-wing and left-wing, simultaneously an anti-semitic traitor to his race and a whingeing Zionist with a chip on his shoulder.

With a nationalistic government in place in 1937 and then with the outbreak of the Second World War, there were more and more restrictions for Jews in their professional life. Sebastian was no longer allowed to practise law, or write for national papers, or have his plays performed. Lesser men might have crumbled, but Sebastian continued writing. Most of the work for which he was remembered for decades was actually written between 1934 and 1944. In his novels and plays he was a real romantic, despite never quite finding fulfilment in love in real life. In my teens I adored the novels The Town with Acacia Trees about a young girl’s emotional awakening, and The Accident, a love story where the nice girl does get the man in the end, even if he was pining after an impossible, difficult love. She does so with a little help from a mountain chalet and some skiing lessons (which describes my youth perfectly).

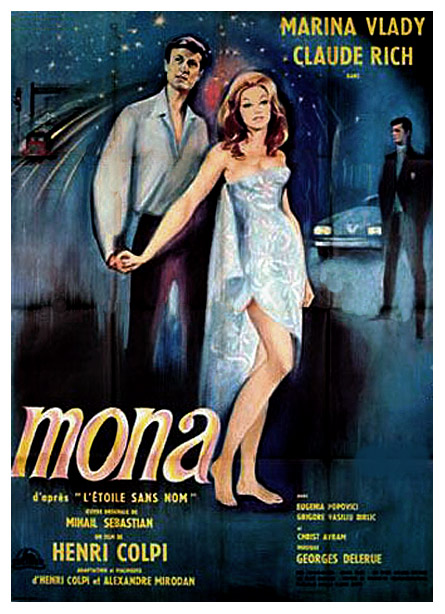

His plays are even better, all are comedies but with a layer of wistfulness and missed opportunities. The Holiday Game is about a group of male friends on holiday who are all in love with the same girl. For a short while, they can pretend to forget stark reality, but alas, the holidays finish far too soon. The Nameless Star is about the embryonic romance between a shy astronomer and the young lady who gets off the train at his station. They spend a magical night together and he names a star he has just discovered after her. But when morning comes, she goes back to her old way of life. There is a French film version of this, starring Marina Vlady as Mona.

He died in 1945, just as the war was ending, at the age of 38, while crossing the street to catch a tram on the way to give his first lecture at university. Although I regret all the books he didn’t have time to write, I can’t help thinking that maybe it was for the best. After so many years of suffering and watching his country succumb to right-wing military regime, I’m not sure he could have coped with a cruel descent into Communist dictatorship.

What a fascinating person, Marina Sofia! Thanks for sharing his background (of which I knew none). I admire authors who can really share their times and people that well, so that you really feel them.

He sounds remarkably modern, even though he writes about events from nearly 80 years ago. It is depressing though, to hear so many arguments that he debunked still being recycled…

Thank you for this lovely post, Marina. I read and loved For Two Thousand Years but knew very little about him. Now I want to read more.

I think anyone who shares me admiration for Orwell will enjoy Sebastian’s essays and diaries. He is equally as unsentimental and almost prescient about the consequences of certain political actions and posturings. His novels are much more sentimental than Orwell’s, although maybe Keep the Aspidistra Flying is quite close to that sense of ‘missed opportunities’ and making the most of imperfection that is so prevalent in Sebastian’s work.

I have just returned from Bucharest, where I fell into a uncomfortable conversation with a guy who accused Mihial Sebastian of being a facist, and a supporter of the Iron Guard. I tried to counter his claims but with little success.

I agree, Marina, a fascinating and an informative post. Thanks for writing about Mihail Sebastian and his brief life and work. One can’t imagine what freethinking writers (like him) and artists went during times of social and political unrest.

I’ve just come across this really poignant passage from his diaries dating from 1938, after the annexation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939: a writer friend of his proposes that they all get together and make a solemn vow that whichever one of them survives the war should edit and publish the manuscripts of all the others. And Sebastian muses: ‘I don’t care so much about my manuscripts. I care more about all the books I won’t get to write in the future.’

Hi Maria,

This is a fascinating piece on Mihail Sebastian – thank you for writing about this important but largely unknown man! I’m from Other Press, the publisher of the English (US edition) translation of For Two Thousand Years. You might be interested to know that we’re publishing another one of the author’s works this March – it’s called “Women.” Please feel free to email me if you’d be interested in an advance copy, or more information.

Regards,

Leah

I saw that you’ll be publishing Women – a collection of novellas, right? I’ll be in touch. And if you are ever thinking of translating his plays… I offer my services.

What a poignant life story. I’ve not read Sebastian – is For Two Thousand Years a good place to start?

Hmm, I should have read this post before reading the review. Oh, well.

He’s an interesting figure and it makes me very curious. Thanks for this post, it brings useful information for readers like me, who don’t know much about Romanian literature.

And I have grown-up with the image of Romania as a dictatorship and it’s hard to shake this negative image. What a waste of talent and culture in all Eastern countries in the 1940s and then Communist years.

Yes, a waste of at least 1-2 generations under Communism. But what was shocking for me personally was that Sebastian shows the dark underside of what was supposedly a glorious golden age in Romanian literature, arts, society – we always looked upon the interwar years with such nostalgia. Undeservedly so, it would appear.

Hello, my translation of ‘The Town with Acacia Trees’ by Mihail Sebastian has just been published. Would you be interested in reviewing it? Thanks, Gabi

https://aurorametro.com/product/the-town-with-acacia-trees/

Cu mare placere!

I have just returned from Bucharest, where I fell into an uncomfortable conversation with a guy who accused Mihail Sebastian of being a fascist and a supporter of the Iron Guard. I tried to counter his claims but with little success.

Clearly someone who has not read enough about that period. Funnily enough, it’s usually the opposite: denying that certain writers had right-wing sympathies at the time (Eliade etc.)