The only expensive hobby I have (other than ordering mochi from the Japan Centre every few months) is book-buying. But sometimes I get lucky and have books given to me by friends. Here is a pile I acquired this month of April – a fairly normal rate monthly rate of acquisition, I would say.

From the top:

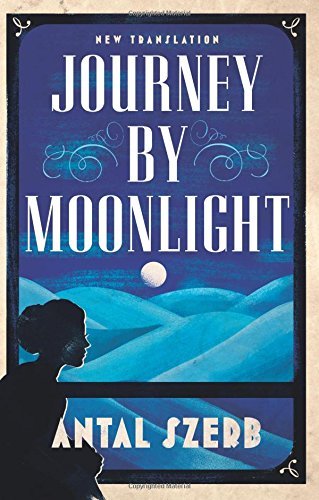

I enjoyed Antal Szerb‘s Journey by Moonlight so much that I ordered several of his other books that have been translated into English, but only this one Oliver VII has arrived thus far, a sort of Prince and the Pauper retelling.

I think Selva Almada’s Not the River got lost in the post when I first ordered it for the International Booker longlist reading, so I had to reorder it, and am very glad I did so, as it was one of my favourite reads from the longlist, and has deservedly been shortlisted too.

Three new books in Romanian published by Cartier, a publishing house from the Republic of Moldova, hand-delivered by the lovely journalist and author Paula Erizanu. Valentina Șcerbani’s Orașul Promis (The Promised City) and Lorina Bălteanu’s Legată cu funia de pământ (Tied with a rope to the earth) are stories of rural families, seen through the eyes of a child, while Gelu Diaconu’s Kaulas is the little-told story of growing up gay in Romania in the 1980s.

Strange, horror-tinged Korean stories appeal to me immensely, and The New Seoul Park Jelly Massacre by Cho Yeeun seems to fall nicely into this category.

To Hell with Poets by Baqytgul Sarmekova is probably the first book from Kazakhstan that I’ll be reading for our London Reads the World Book Club.

I was supposed to receive an ARC of The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft, but that too might have gone missing in the post. A book about translators in primeval forests in Europe by one of my favourite translators? I’ve heard the author speak about it too online. Bring it on! This one was very kindly passed on by my blogger friend from Lizzy’s Literary Life.

Kakuta Mitsuyo is a very popular author about contemporary Japanese women’s lives, but hasn’t been translated all that much into English. However, several of my blogger friends who are interested in Japanese literature have featured her, for example Tsundoku Reader.

Vincent and Theo: The Van Gogh Brothers by Deborah Heiligman I saw reviewed recently on The Scientific Detective’s blog – and, since I am so fond of Van Gogh’s work, I had to get it.

I have to admit that I am at that stage in my bookish love in which I need to get rid of books just as fast if not faster as I acquire them, for fear that it will cost a fortune to ship them abroad, and that I’ll have no room to store them in my much smaller next house (flat). Can I help it if I fall so easily into temptation – as soon as a publisher sends me a newsletter, as soon as I attend an event, as soon as I read a review? Although I use libraries extensively too, I have to repeat to myself: ‘You do not have to buy every single book that sounds interesting.’

Having said that, I might have a wander through the bookshops of Berlin as well next week.