Time for my favourite meme: the chain of six books, linked in some way from a given starting point, as hosted by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best. The starting point this month is Rachel Cusk’s Second Place, which is loosely based on DH Lawrence stay as a houseguest in Mexico (Mabel Doge Luhan being the unfortunate host; she wrote about it in Lorenzo in Taos). A woman invites a famous artist to use her guesthouse in the remote coastal landscape where she lives with her family, hoping that his artistic vision will somehow infuse and clarify her own life. I have not read it yet, but am curious to do so.

It would be far too easy to move onto DH Lawrence after this, but instead I will move to other authors whom I originally liked a lot, but whom I’ve stopped following quite so closely over recent years. Yes, I read all of Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, but was less engaged with it than I was with her earlier work. Stand up, Mr Karl Ove Knausgård! I was intrigued and captivated by the first two volumes of his six-volume My Struggle (A Death in the Family and A Man in Love), partly because it felt like a novelty for a man to be writing about such intimate domestic details. But I was more lukewarm about volumes 3 and 5 and didn’t bother with the rest.

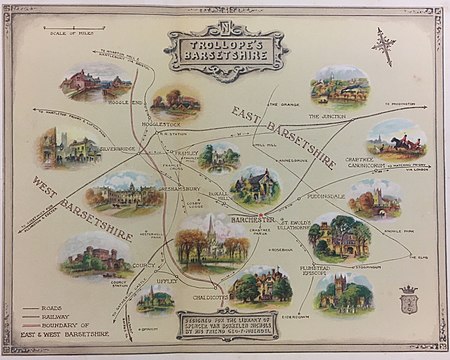

One series of six novels which I keep meaning to read but never quite get muster the courage is The Chronicles of Barsetshire by Anthony Trollope. I’ve read a couple of his freestanding works a long, long time ago, and was never quite as enamoured of him as I was of Wilkie Collins or Dickens. The map below of the fictional county of Barsetshire does tempt me though – I can never resist a map.

Trollope famously worked for most of his life in the Post Office (in fairly senior positions, I should add), and this ‘keeping of the day job’ is what he has in common with the next writer. Anton Chekhov remained a doctor throughout his life, alongside his writing. I will refer to his play Uncle Vanya, because it is one in which he features the overworked, pessimistic and resigned doctor Astrov.

Time for a woman after so many men featured in this chain – and of course the word ‘Uncle’ in the title reminds me at once of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Conceived as an anti-slavery novel in 1852 and believed to have contributed to some degree to the American Civil War, it has been criticised more recently for perpetuating stereotypes about black people. However, it was one of the huge bestsellers of the 19th century and was adapted many times as a play, musical or film.

Yet it wasn’t the most translated book from the United States in this recent BookRiot ‘most translated book from each country’ infographic, which has both amused and incensed me. I felt that it was somewhat unfair that Romania’s prime export was a perfectly competent but average book published 4-5 years ago and written in English, set in the US, designed to very cynically exploit the foreign markets. But that is nothing compared to the fact that the US prime export is Ron Hubbard’s The Way to Happiness (although there is a good reason for that – it was paid-for translation and distribution, so a big push on the supply side, rather than huge demand).

I could pick another book from the above infographic (and am pleased to see that The Little Prince, Tintin, Pinocchio, Treasure Island and Pippi Longstocking are there – good old children’s classics, what would we do without them?), but that would be too easy, so instead I’ll pick a book by another religious person, one much more palatable to me. Ron Hubbard was the founder of Scientology, but this final writer is a woman, Mariana Alcoforado, a Portuguese nun who wrote the famous, wildly passionate Letters from the Portuguese (beautifully translated by Rilke into German, for example). Her authorship has since been contested but the tale of betrayed love is timeless and universal.

A bit of a strange journey this time, not always with authors I appreciate: from Norway to a provincial town in England, on to a Russian estate in the 1890s to the American South in the 1850s, a self-help book that claims to be truly international and a love affair that transcends Catholic convents or Portuguese borders. Do share where your Six Degree journey might take you this month!